or data related to this building

to enter

Bulletin

31.05.2024

Collective Practice: Reading Circle 1

The SAT Research initiative invites you to our community building programme ‘Collective Practice’, beginning with a series of fortnightly reading circles where we will gather to read, learn and unlearn together. Collective practice is aimed to hold space for exercising alternative actions and approaches to research. By sharing literature, knowledge and experiences we hope to challenge the silos of socio-urban discourse and relate to others through connection, active understanding and solidarity.

Our first reading circle will center the book ‘Palestinian Walks’ by Raja Shehadeh. Set across six walks taken between 1978 and 2006, the book traverses the expropriation of native lands to illegal settlements.

28.03.2024

Resident Focus Group_Summer 2024

The SAT Research initiative, ‘Living Continuity: a collective inquiry’, invites you to participate in our ongoing activities on place-making and community building. Join us to envision and express our relationship to the city in our resident focus group sessions this summer where we will create new tools and processes to engage in the city. If you are a resident of Sharjah and interested in contributing to collective learning on our relationship to our neighborhoods and communities, we’d love to hear from you. Register your interest to participate in this series of meetings that will be planned from May-July 2024 to receive details and updates.

18.02.2023

Living Continuity Sessions 5 and 6

Panel 1: The Urgency of People-Centred Planning and Praxis-based Alternatives

For this session, we look critically inwards and explore work that challenges the current frontiers of architecture and urbanism. How can praxis enable critical engagement, and what does it reveal around current issues of access, exclusion, precarity and participation in neighbourhood planning?

Panelists: Arshiya Syed, Jason Carlow, Najia Fatima, Paulina Yeal Cho

Convener: Sharmeen Inayat

Discussant: Beatriz Itzel Cruz Megchun

Panel 2: Participatory Research and Lessons in Community Interdependence

In this session, we will explore the importance of amplifying and enabling community voices. What are the challenges, incremental and transformative actions necessary to challenge current systems that exclude and marginalise the global majority? How can modes of research support modes of resistance?

Panelists: Maitha Alhammadi, Marcos Parga, Ailo Ribas

Convener: Sharmeen Inayat

Discussant: Beatriz Itzel Cruz Megchun

We are committed to fostering community building through ongoing collaborative engagement and critical discourse. Registration for individuals who are interested to attend and participate is open. View programme details here.

02.02.2023

Spring 2023 Programme Announcement

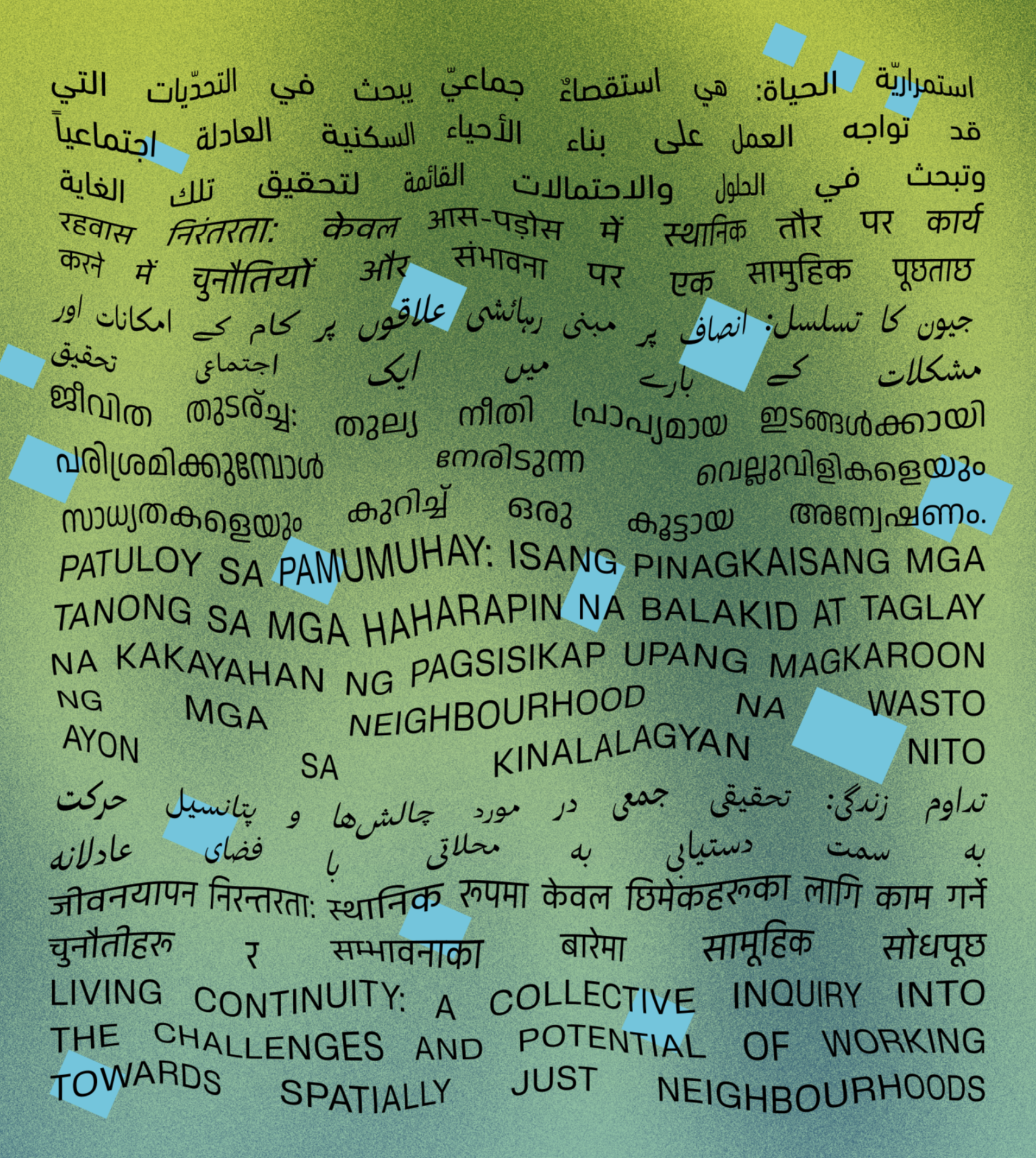

Living Continuity is a collective inquiry into the challenges and potential of working towards spatially just neighbourhoods. In current urban policy debates, the neighbourhood has emerged as an important scalar construct to understand the systems and processes that shape communities and ecosystems. This calls for re-examining the denotations and connotative dimensions of the terms ‘neighbourhood’, and ‘community’ beyond the romanticised and the normative. In the global context of pervasive neoliberal urbanism, cities that are planned and grow on principles of zoning warrant accelerated segregation, expulsion and homogenization. Urban expansion and renewal thus yields disproportionate access to and distribution of environmental wellness, urban commons, social health and mobility. The tension between renewal vs expansion which occurs at this scalar level also raises questions on how to secure lived continuity, intersectional diversity, and social cohesion. How can interlocutors, respondents and residents facilitate and advocate for inclusive, decolonial and sensitised discourses around urban policy and education given socio-political limitations and challenges?

This line of inquiry will continue to be explored through a research exhibition featuring roundtables, knowledge exchange and supplementary tools from February 18th–April 30th 2023 at the Al Jubail Vegetable Market in Sharjah and online on the SAT Research Initiative webpage. We will reflect on how to broaden our understanding of praxis-based alternatives as well as how to amplify people-centred approaches through insights on interdependence, plurality and spatial practice. Stay posted for announcements and details on how you can participate.

Living Continuity is the inaugural discursive series organized by the SAT Research Initiative, one of the core programmes of the Sharjah Architecture Triennial. The project is curated by Sharmeen Inayat, Research Curator of SAT Research Initiative and features contributions from Ailo Ribas, Alfonse Chiu, Arshiya Syed, Beatriz Itzel Cruz Megchun, Bhoomika Ghaghada, Haitham Issam, Jason Carlow, Khaled Alawadi, Khaled Galal Ahmed, Maitha Alhammadi, Marcos Parga, Mona El-Mousfy, Najia Fatima, Paulina Yeal Cho, Yasser Elsheshtawy, Tariq Miah, Martin Abbott + Jennifer Minner, Frederik Weissenborn + Aude Azzi, Juan Roldan, Bhakti More, George Katodrytis, Muhammad Aziz, Abu Dhabi Public Spaces Project, Jumanah Abbas, Leon Duval, and Ashraf Salama + Florian Wiedmann.

12.08.2022

Register to attend Living Continuity Seminar Session 4 (Online) to be held on August 24th, 2022

SAT Research seminars resume with Session IV which will convene online on August 24th, 2022. Living Continuity is a collective inquiry on the challenges and opportunities of working towards spatially just neighbourhoods. Session IV aims to explore the temporal dimension of housing through indicators of social cohesion and socio-spatial attributes that resist transience. Dr Yasser Elsheshtawy expands on a case study analysis of folk houses in the UAE, how they became a testament of inhabitants asserting their presence and rootedness in the midst of a constantly changing cityscape and the lessons they provide. Dr Bhakti More shares her study comparing four residential neighbourhoods in Dubai to understand the concept of residential stability, social cohesiveness and the influence of shared spaces amongst expatriate residents in neighbourhoods in Dubai.

Committed to fostering community building through ongoing collaborative engagement and critical discourse, registration for individuals who are interested in attending and participating in the discussion with the invited speakers is open. To RSVP, please send expressions of interest to info@sharjaharchitecture.org. The session will be held online on August 24 at 6:00 PM GST. Confirmations of your registration along with the webinar link will be sent by email on August 21.

02.06.2022

Call for Proposals (Essay Abstracts)

This call for proposals invites contributions to the first instalment of SAT Research. Authors of accepted essays will be commissioned to develop their work for publication. The publication will feature the work of invited contributors as well as authors selected through this open call process. Select commissions may be invited to present their work at a symposium to take place in December 2022 in Sharjah.

Living Continuity is an invitation to begin a collective inquiry on the challenges and potentialities of working towards a socially and ecologically just urban future beginning at the scale of the neighbourhood. Subject matter that will be explored includes but is not limited to:

1. Social and ecological issues as a result of the development of homogenised neighbourhoods and accelerated land use.

2. Proximity and access to neighbourhood amenities and green spaces.

3. Spatial practices that shaped traditional neighbourhoods. In port cities such as Sharjah, this included responsive and adaptive typologies, urban diversity and compactness.

4. The impact of neoliberal and colonial forces on local conditions through shifting value systems and expeditious expansion.

5. Social rituals reimagined as alternatives to current dominant models.

6. Readings across time, sectors and communities to better understand the issues around and solutions to spatial distribution and access.

7. Social conduits and urban voids as tools of collective efficacy and interdependency.

Format and Focus

Proposals must include a 250-300 words abstract and author biography.

Proposals for the following essay formats are invited to submit:

1. Expository Essay of 2500 to 5000 words. Expository essays are reserved for research-based work focused on Sharjah and the United Arab Emirates or work that draws strong comparisons and parallels to local conditions.

2. Argumentative or Position Essay of 1500 to 3000 words. Position essays are not limited to geographic scope and are open to writing across research, practice and education that provokes new perspectives and offer a critical lens for the subject matter.

3. Visual Essay or Data Story of 5 to 20 visuals: Visual essays are not limited to geographic scope and are welcome to illuminate knowledge and findings that support key ideas in an artistic capacity or through data journalism.

Key Dates [UPDATED]

July 15, 2022: Deadline to submit abstracts and proposals

August 09, 2022: Notifications sent to authors of selected proposals

November 05, 2022: Deadline to submit the full-length drafts

November 30, 2022: Editorial review sent to authors

December 21, 2022: Deadline to submit final essays

Submission

Authors must be able to furnish requested permissions for any third-party materials included in their paper.

This is a multi-disciplinary initiative that strives to be inclusive. Contributions from fields beyond the realm of architecture and urbanism including the social sciences and the arts are strongly encouraged. New perspectives on methodologies, marginalised voices outside the realm of academic research and local knowledges from the Global South are also strongly encouraged.

All submission documents must be sent as a Microsoft Word file via email to the editor at sharmeen@sharjaharchitecture.org.

12.03.2022

Register to attend SAT Research Launch – Living Continuity, Seminar Sessions 1, 2 and 3

SAT Research's first seminar will be held on March 19th, 2022. Titled, Living Continuity: A Collective Inquiry, This instalment focuses on local challenges to preserving robust, sustainable and inclusive neighbourhoods. Questions we will be asking include: How can we reimagine rapidly eroding regional sensitivities and knowledge systems? How can architecture and urbanism practitioners, educators and stakeholders begin to tackle precipitous global urbanization while operating in a vast field of economic, political and social demands? Committed to growing a repository of local knowledge production and fostering community-building through ongoing collaborative engagement, we invite individuals who are interested in participating to join our invited speakers and discussants for the full-day event. Please send expressions of interest by March 15. Seats are limited and confirmations of your registration will be sent by email on March 17.

Session I, alternatives to urban expansion, will open the discussion with Mona El-Mousfy’s insights stemming from her research-based practice and the application of adaptive reuse methods in Sharjah City, and Khaled Galal Ahmed, who offers alternative solutions to social housing in the UAE to challenge the prevalence of Western housing models. Session II, urban networks as critical space, features Khaled Alawadi’s morphological mappings of alleyways in Abu Dhabi and Dubai revealing the potential impact of these micro-networks and Beatriz Itzel Cruz Megchun’s framework for design for social interdependence. Session III, forms of community expulsion and exclusion, will conclude the day’s sessions with Bhoomika Ghaghada’s analysis of the cultural expulsion in the Karama neighbourhood of Dubai that questions what is lost when something is redeveloped and Juan-Roldan Martin’s observations of urban appropriation and rituals established by inhabitants that defy constructs of imported Western park models in the UAE.

The event will take place at the disused Al Jubail Vegetable Market in Sharjah in a segment of the semi-open, naturally ventilated building. The site, previously slated for demolition after the market was relocated, is currently being programmed by the Sharjah Architecture Triennial and the Sharjah Art Foundation for temporary events and exhibitions. It is planned to be the future home of SAT Research among other institutional activities and public programmes.

Powered by Froala Editor

Repository

Powered by Froala Editor

Decentralizing Domesticities

Marcos Parga – Living Continuity Session VI

Seminar

The Vast Lands of Al Rahba City

Maitha Alhammadi – Living Continuity Session VI

Seminar

Weedy Strategies: Growing Alternative Ecological Practices

Ailo Ribas – Living Continuity Session VI

Seminar

Neoliberal spatial transformation and the lessons of Hyderabad

Arshiya Syed – Living Continuity Session V

Seminar

Sharjah’s Industrial Villages: Documenting Informal Domestic Networks

Jason Carlow – Living Continuity Session V

Seminar

Asymmetries of Caste and Waste Management in Urban Pakistan (and Beyond)

Najia Fatima – Living Continuity Session V

Seminar

Welcome to Bom Retiro

Paulina Yeal Cho – Living Continuity Session V

Seminar

The Sha’abi House Revisited: Resisting Transience in the UAE

Dr Yasser Elsheshtawy – Session IV

Webinar

Urban Planning, Neighbourhoods & Social Cohesiveness

Dr Bhakti More – Living Continuity Session IV

Webinar

Adaptive Reuse Potentialities in Sharjah

Mona El-Mousfy – Living Continuity Session I

Seminar

Fareej in the Sky: Vertical Social Housing in the UAE

Dr Khaled Galal Ahmed – Living Continuity Session I

Seminar

Practice-place and space: narrations of urban memories

Dr Beatriz Itzel Cruz Megchun – Living Continuity Session II

Seminar

Alleyways: Mapping a Forgotten Urban Form Element

Dr Khaled Al Awadi – Living Continuity Session II

Seminar

Karama: An Immigrant Neighbourhood Transformed

Bhoomika Ghaghada – Living Continuity Session III

Seminar

Outdoor Rooms: domesticated landscapes

Juan Roldan Martin – Living Continuity Session III

Seminar

Introduction to the SAT Research Initiative Living Continuity

Sharmeen Azam Inayat

Discussion

Decentralizing Domesticities

Marcos Parga – Living Continuity Session VI

Living Continuity is a collective inquiry on the challenges and opportunities of working towards spatially just neighbourhoods. Session VI explores the importance of amplifying and enabling community voices. What are the challenges, incremental and transformative actions necessary to challenge current systems that exclude and marginalize the global majority? How can modes of research support modes of resistance? Marcos Parga presents his research on decentralized domesticities. Inspired by the isolation many experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, and reflecting on the scarcity of housing in many urban centers, he attempts to imagine new models that allow residents to reclaim the architectures they have been given.

Marcos Parga, Ph.D., is an international, award winning architect and designer, Assistant Professor at Syracuse University School of Architecture and founding principal of MAPAa Estudio, a design practice based in Syracuse, NY (USA) and Madrid (Spain). His research explores alternative ways of practicing and evaluating the architecture of the collective, considering the impact of contemporary environmental, political, economic, and social issues on the built environment and its influence on creating the appropriate conditions for certain social changes to occur. Through his current work he investigates emerging models of urban commons and new forms of shared domesticities, questioning the political role of architects in shaping those alternative realities.

Powered by Froala Editor

The Vast Lands of Al Rahba City

Maitha Alhammadi – Living Continuity Session VI

Living Continuity is a collective inquiry on the challenges and opportunities of working towards spatially just neighbourhoods. Session VI explores the importance of amplifying and enabling community voices. What are the challenges, incremental and transformative actions necessary to challenge current systems that exclude and marginalize the global majority? How can modes of research support modes of resistance? Maitha Alhammadi presents her semi-autoethnographic research on Al Rahba City in Abu Dhabi, reflecting on the evolution of the suburban city and the changing relationship women and girls have had to it.

Maitha Alhammadi is a recent Architecture graduate from the American University of Sharjah (AUS). She is currently working as a landscape designer on multiple infrastructural projects with Parsons in Abu Dhabi, the UAE. Driven by her keen interest in nature, art, sciences, and community wellbeing, she is working towards promoting wellness and more physical activity in the UAE. Besides advocating for community-based wellness centers within her community, her current research examines the landscapes's socio-ecological capacities and began whilst seeking knowledge towards revitalizing the cities of the UAE in her last semester at AUS.

Powered by Froala Editor

Weedy Strategies: Growing Alternative Ecological Practices

Ailo Ribas – Living Continuity Session VI

Living Continuity is a collective inquiry on the challenges and opportunities of working towards spatially just neighbourhoods. Session VI explores the importance of amplifying and enabling community voices. What are the challenges, incremental and transformative actions necessary to challenge current systems that exclude and marginalize the global majority? How can modes of research support modes of resistance? Ailo Ribas shares her fieldwork and experiences with alternative ecology practices in the Bethnal Green Nature Reserve in London, UK, asking how such practices can nurture wellbeing and disrupt a city culture of production, consumption, and excess.

Ailo Ribas is a trans writer, researcher, community organiser and archivist. Her work seeks to build networks of knowledge-sharing and storytelling within and between communities around the topics of trans care, plants, urban ecologies and witchcraft. She is a graduate of the Centre for Research Architecture at Goldsmiths University and a founding member of the artist research collective Al-Wah'at.

Powered by Froala Editor

Neoliberal spatial transformation and the lessons of Hyderabad

Arshiya Syed – Living Continuity Session V

Living Continuity is a collective inquiry on the challenges and opportunities of working towards spatially just neighbourhoods. Session V looks critically inwards to explore work that challenges the current frontiers of architecture and urbanism. How can praxis enable critical engagement, and what does it reveal around current issues of access, exclusion, precarity and participation in neighborhood planning? Arshiya Syed explores the impact of the neoliberal turn in the Indian economy on urban development since the late 1990s. She focuses on the city of Hyderabad to show how neoliberalism has led to a privileging of profit-driven mega projects, including infrastructure and tourism developments.

Arshiya Syed is the founder of Studio Maqam, an architecture and urban design firm in Hyderabad, India. She holds a Masters degree in Urban Design from the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi, and was also an Urban Fellow with the Indian Institute of Human Settlements, Bangalore. Arshiya has a decade of experience in architecture and urban design practice, and is a visiting faculty member, teaching urban design and housing studios in several architecture schools. Her research interests lie in affordable housing, public space design, and the historical development of cities. She is currently writing a book on the experience and architecture of the Hajj in the city of Mecca.

Powered by Froala Editor

Sharjah’s Industrial Villages: Documenting Informal Domestic Networks

Jason Carlow – Living Continuity Session V

Living Continuity is a collective inquiry on the challenges and opportunities of working towards spatially just neighbourhoods. Session V looks critically inwards to explore work that challenges the current frontiers of architecture and urbanism. How can praxis enable critical engagement, and what does it reveal around current issues of access, exclusion, precarity and participation in neighbourhood planning? Jason Carlow examines Sharjah’s industrial zones, analyzing how working-class, migrant ‘bachelors’ transcend the limited infrastructure available to them and use informality to create spaces of leisure, commerce, and housing.

Jason Carlow holds a BA in Visual and Environmental Studies from Harvard University and an MArch from Yale University, and is Associate Professor of Architecture at American University of Sharjah. Prior to AUS, he taught architecture, with a focus on compact housing and urban informality, at University of Hong Kong for ten years. His recent work focuses on issues surrounding housing for dense urban environments. He is co-author of the forthcoming book, Cities of Repetition: Hong Kong’s Privately Developed Housing Estates (AR+D Publications) and a book chapter entitled, “Industrial Promises: New Speculative thinking for Sharjah’s industrial districts,” in Urban Modernity in the Contemporary Gulf: Obsolescence and Opportunity, edited by Roberto Fabbri and Sultan Sooud Al-Qassemi (Routledge). Carlow’s design and research work has been published and exhibited internationally at the Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture in Shenzhen and Hong Kong, Venice Biennale of Architecture, and Beijing Architecture Biennial, and he is the recipient of the 2020 AIA/ACSA Housing Design Education Award.

Powered by Froala Editor

Asymmetries of Caste and Waste Management in Urban Pakistan (and Beyond)

Najia Fatima – Living Continuity Session V

Living Continuity is a collective inquiry on the challenges and opportunities of working towards spatially just neighbourhoods. Session V looks critically inwards to explore work that challenges the current frontiers of architecture and urbanism. How can praxis enable critical engagement, and what does it reveal around current issues of access, exclusion, precarity and participation in neighbourhood planning?. Najia Fatima discusses the status of sanitation workers in urban Pakistan, highlighting how class, caste, and religious identity intersect to marginalize workers, and how urban design and housing conditions exacerbate this marginalization.

Najia Fatima is a graduate of M.S. Critical, Curatorial, and Conceptual Practices of Architecture at the Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. Fatima also has an independent art practice that engages with themes of occupation, displacement, and geopolitical tensions in contemporary South Asia; her writing, considering how the built environment manifests structural inequality, has been published in various magazines. She earned her B.A. in Architecture and Visual Studies from the University of Toronto.

Powered by Froala Editor

Welcome to Bom Retiro

Paulina Yeal Cho – Living Continuity Session V

Living Continuity is a collective inquiry on the challenges and opportunities of working towards spatially just neighbourhoods. Session V looks critically inwards to explore work that challenges the current frontiers of architecture and urbanism. How can praxis enable critical engagement, and what does it reveal around current issues of access, exclusion, precarity and participation in neighbourhood planning? Paulina Yeal Cho examines the Bom Retiro district in Sāo Paulo, Brazil, reflecting on its rich migrant history, how the neighborhood has developed into a Koreatown, and how this relates to the rise of hallyū and Korean soft power.

Paulina Yeal Cho is the daughter of a single Korean migrant mom. She was born in Brazil and spent her youth between São Paulo and Buenos Aires. Paulina graduated from Tsinghua University with a master's degree in Global Affairs and University of Sao Paulo with a bachelor's in Law. She was a researcher on Green Gentrification, Ecological Urbanism, and Capitalization of Nature at Escola da Cidade. Currently, Paulina is working at Systemiq, developing projects that promote a nature-based, people-centered and sustainable approach in the region.

Powered by Froala Editor

The Sha’abi House Revisited: Resisting Transience in the UAE

Dr Yasser Elsheshtawy – Session IV

Living Continuity is a collective inquiry on the challenges and opportunities of working towards spatially just neighborhoods. Session IV aims to explore the temporal dimension of housing through indicators of social cohesion and spatial qualities that resist transience. Dr. Yasser Elsheshtawy expands on a case study analysis of folk houses in the UAE, how they became a testament to inhabitants asserting their presence and rootedness in the midst of a constantly changing cityscape, and the lessons they provide.

Yasser Elsheshtawy is an independent scholar, an Adjunct Professor of Architecture at Columbia University, GSAPP, and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, DC. He was a Professor of Architecture at United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, where in addition to teaching he also ran the Urban Research Lab. He was appointed as the curator for the UAE Pavilion at the 15th Venice Architecture Biennale in 2016. Considered an authority on urbanism in the region, his scholarship focuses on urbanization in developing societies, informal urbanism, urban history, and environment-behavior studies, with a particular focus on Middle Eastern cities. He authored a series of books and publications including “Dubai: Behind an urban spectacle” (ranked no. 1 on Amazon under the 'United Arab Emirates History' category in September 17). His blog dubaization has been hailed by The Guardian as one of the notable city blogs in the world. Elsheshtawy is currently working on a book about the Arab Gulf City titled Temporary Cities. He has been appointed as a Visiting Professor at Université Sorbonne Paris Cité (Fall 2017). He was a Visiting Scholar at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, DC to pursue his research on urbanization in the Gulf and work on his book during Spring 2018.

Powered by Froala Editor

Urban Planning, Neighbourhoods & Social Cohesiveness

Dr Bhakti More – Living Continuity Session IV

Living Continuity is a collective inquiry on the challenges and opportunities of working towards spatially just neighborhoods. Session IV aims to explore the temporal dimension of housing through indicators of social cohesion and spatial qualities that resist transience. Dr. Bhakti More shares her study comparing four residential neighborhoods in Dubai to understand the concept of residential stability, social cohesiveness, and the influence of shared spaces amongst expatriate residents in neighborhoods in Dubai.

Dr. Bhakti More is a Chairperson, School of Design & Architecture, Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE) Dubai Campus. She has pursued her doctoral studies at the School of Built Environment, University of Salford, Manchester, UK, and her area of research is 'Urban planning, neighborhoods and social cohesiveness: A socio-cultural study of expatriate residents in Dubai. She received CIOB Best Research Paper Award for the most innovative research for her paper titled "Expatriate Housing and the Social Fabric in Dubai" during the 12th International Post Graduate Research Conference, University of Salford Manchester UK in 2015. Dr. Bhakti has presented papers at International Conferences in Portland, USA, Fukuoka, Japan, and Dubai. She is a coordinator for Manipal Environment and Conservation Students Club received consecutive awards for Best Sustainable Green Campus Audit and Best Sustainability Action Project from Environment Agency Abu Dhabi and has led research and innovation project for MAHE Dubai team "Tawazun" for building net zero home for Solar Decathlon ME 2021 and is part of the core team for preparing Climate Action Plan for MAHE Dubai. Dr. Bhakti is an ambassador for 'Woman in Construction' for the Big 5, Dubai, and is President of Manipal Employee Resource Group, Diversity & Inclusion. She is a mentor for the E7 Daughter of Emirates Program and Link Mentorship Program in the UAE.

Powered by Froala Editor

Adaptive Reuse Potentialities in Sharjah

Mona El-Mousfy – Living Continuity Session I

Living Continuity, the first instalment of SAT Research’s Seminar Series, is an invitation to begin a collective, multiscalar and contextualized inquiry on the challenges and potentialities of working towards a socially and ecologically just urban future. Beginning at the scale of the neighbourhood, the first seminar focuses on local challenges to preserving robust, sustainable and inclusive neighbourhoods.

Session I on alternatives to urban expansion features Mona El-Mousfy’s insights into her research-based practice and the application of adaptive reuse in Sharjah City, and Khaled Galal Ahmed, who offers alternative solutions to social housing in the UAE to challenge the prevalence of Western housing models.

Mona El-Mousfy is an architect and the founder of SpaceContinuum, a research-based architecture practice that explores the relation between space, shared social practices and socio-cultural conditions. El-Mousfy is the Advisor to the Sharjah Architecture Triennial and played a key role in founding the initiative in 2017. She is also the Architecture Consultant for the Sharjah Art Foundation where she has worked on several projects including the successive editions of the Sharjah Biennial since 2005.

El-Mousfy is currently engaged in various adaptive reuse projects leading a team of architects at the Sharjah Art Foundation and the Sharjah Architecture Triennial. Among other projects, she designed the SAF Art Spaces Al Mureijah, 2013, which was shortlisted for the 2019 Agha Khan award for Architecture. Her most recent adaptive reuse project is the Flying Saucer, 2020, where she has restored the original mid-70s character of the building while introducing a new outdoor public space and a lower-level community space around a sunken courtyard.

El-Mousfy has previously taught at the College of Architecture Art and Design, American University of Sharjah, where she had a full-time position from 2002 to 2014.

Powered by Froala Editor

Fareej in the Sky: Vertical Social Housing in the UAE

Dr Khaled Galal Ahmed – Living Continuity Session I

Living Continuity, the first instalment of SAT Research’s Seminar Series, is an invitation to begin a collective, multiscalar and contextualized inquiry on the challenges and potentialities of working towards a socially and ecologically just urban future. Beginning at the scale of the neighbourhood, the first seminar focuses on local challenges to preserving robust, sustainable and inclusive neighbourhoods.

Session I on alternatives to urban expansion features Mona El-Mousfy’s insights into her research-based practice and the application of adaptive reuse in Sharjah City, and Khaled Galal Ahmed, who offers alternative solutions to social housing in the UAE to challenge the prevalence of Western housing models.

Dr Khaled Galal Ahmed is Associate Professor and the Coordinator of the Architectural Engineering Master and PhD Programs at UAEU. Dr Khaled got his PhD from the Welsh School of Architecture, Cardiff University, UK. He worked as an architect and urban designer and his research interest is related to sustainable architecture, urbanism and housing especially in Socio-Cultural Impact, Urban Modeling Simulation, Walkability, Urban Morphology and Energy Efficiency, Community Participation, and Urban Resilience. He published his research work in various international journals, conferences proceedings and book chapters. Dr Khaled teaches undergraduate and graduate courses related to architectural, urban and housing design. He has supervised several Master theses and PhD Dissertations at Mansoura University, Egypt and the UAE University. Dr Khaled has several articles in local and regional newspapers and magazines including National Geographic Arabia and has been honoured for his various contributions from the Minister of Happiness and Wellbeing, Abu Dhabi Municipality, Sheikh Zayed Housing Program, Al Ain Municipality, Fujairah Municipality, and Directorate of Planning and Survey, Sharjah. Recently Dr Khaled won the UAEU Chancellor’s Innovation Award in Education- 6th Cycle 20-21. He also won the College of Engineering Award in University and Community Services, Academic Year 2020-2021.

Powered by Froala Editor

Practice-place and space: narrations of urban memories

Dr Beatriz Itzel Cruz Megchun – Living Continuity Session II

Living Continuity, the first instalment of SAT Research, is an invitation to begin a collective, multiscalar and contextualized inquiry on the challenges and potentialities of working towards socially and ecologically just neighbourhoods. It is motivated by observations on two key emerging issues: homogenized urban zones and dormitory towns that are expanding the city's footprint at an exponential rate and the erosion of social cohesion, inclusion and lived continuity.

Session II explored urban networks as critical space in neighbourhoods, the potential impact of micro-networks and the possibilities of designing for collective efficacy and interdependence.

Beatriz Itzel Cruz Megchun shares her research focused on how design intersects with other disciplines to reveal, examine, and transform values, practices, processes, systems, or narratives. Her work reveals how people use social spaces to create community, a sense of identity and belonging. This fact supports the need to shift the current approach to empower those that inhabit a space to participate and contribute directly to its design.

Beatriz Itzel Cruz Megchun is an Assistant Professor of Design and Innovation at the Pamplin School of Business at the University of Portland. Previously, she was an Assistant Professor in Design Management in the College of Architecture, Art and Design at the American University of Sharjah. She obtained her PhD at Staffordshire University, UK, in Design and Innovation. She was awarded a post-doctoral research fellowship at the Centre of Applied Business Research to study design in the decision-making process of entrepreneurs of technology-based enterprises. Her educational content addresses diversity, inclusion, equity and global citizenship in the business context. She has over 15 years of experience consulting in the creative, manufacturing, and new technology industries worldwide. She also participates in projects with non-governmental organizations and governmental institutions addressing social inequalities.

Powered by Froala Editor

Alleyways: Mapping a Forgotten Urban Form Element

Dr Khaled Al Awadi – Living Continuity Session II

Living Continuity, the first instalment of SAT Research, is an invitation to begin a collective, multiscalar and contextualized inquiry on the challenges and potentialities of working towards socially and ecologically just neighbourhoods. It is motivated by observations on two key emerging issues: homogenized urban zones and dormitory towns that are expanding the city's footprint at an exponential rate and the erosion of social cohesion, inclusion and lived continuity.

Session II explored urban networks as critical space in neighbourhoods, the potential impact of micro-networks and the possibilities of designing for collective efficacy and interdependence.

In this seminar, Dr Khaled Al Awadi expands on a study that identifies alleys as a critical space, especially at the neighbourhood scale. Alleys have been neglected in the definition of urban form even though they have existed since antiquity and have served a variety of vital purposes for the community.

Khaled Alawadi is the first UAE national scholar to specialize in the design of sustainable cities, Dr. Alawadi is Assistant Professor of Sustainable Urbanism at Khalifa University, Masdar Campus, where he founded the MSc. in Sustainable Critical Infrastructure program. He is a trained architect, planner and urban designer whose research is devoted to urban design, housing and urbanism, especially the relationships between the built environment and sustainable development.

Powered by Froala Editor

Karama: An Immigrant Neighbourhood Transformed

Bhoomika Ghaghada – Living Continuity Session III

Living Continuity, the first instalment of SAT Research, is an invitation to begin a collective, multiscalar and contextualized inquiry on the challenges and potentialities of working towards socially and ecologically just neighbourhoods. It is motivated by observations on two key emerging issues: homogenised urban zones and dormitory towns that are expanding the city's footprint at an exponential rate and the erosion of social cohesion, inclusion and lived continuity.

Session III focuses on how macro-forces and neoliberal urbanism have increased the risk of community expulsion and resulted in varying forms of community exclusion. Bhoomika Ghaghada presents her research on the downtown neighbourhood of Karama and how its landscape, demographic composition, and cultural identity have been transformed through redevelopment since 2015, leading to cultural expulsion. Developed during her MA in Media Studies at Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, in 2019, her thesis centres the embedded South Asian community of Karama as it undergoes erasure.

Bhoomika Ghaghada is a writer and independent researcher, born and raised in the UAE. She writes about gender, urban spaces, and media, focusing on structural inequalities and their everyday manifestations. Her writing has appeared in Jadaliyya, Postscript Magazine, and Unootha Mag. She is the Co-Founder of Gulf Creative Collective, a non-profit initiative helping creatives in the UAE re-evaluate notions of value, advocate for themselves in the workplace, and find refuge, care and community.

Powered by Froala Editor

Outdoor Rooms: domesticated landscapes

Juan Roldan Martin – Living Continuity Session III

Powered by Froala Editor

Introduction to the SAT Research Initiative Living Continuity

Sharmeen Azam Inayat

Living Continuity, the first instalment of SAT Research, is an invitation to begin a collective, multiscalar and contextualized inquiry on the challenges and potentialities of working towards socially and ecologically just neighbourhoods. It is motivated by observations on two key emerging issues: homogenized urban zones and dormitory towns that are expanding the city's footprint at an exponential rate and the erosion of social cohesion, inclusion and lived continuity.

Sharmeen Azam Inayat is a cultural worker. She is currently working with the Sharjah Architecture Triennial on charting and establishing the SAT Research initiative as Research Curator.

Powered by Froala Editor

Contributors

Contributors

Ailo Ribas

Arshiya Syed

Dr Beatriz Itzel Cruz Megchun

Dr Bhakti More

Bhoomika Ghaghada

Jason Carlow

Juan Roldan Martin

Dr Khaled Alawadi

Dr Khaled Galal Ahmed

Maitha Alhammadi

Marcos Parga

Mona El-Mousfy

Najia Fatima

Paulina Yeal Cho

Dr Yasser Elsheshtawy

Research Curator

Sharmeen Inayat

Researcher and Project Coordinator

Fabya Mohammed

Production Coordinator

Abanob Ataia

Graphic design

Layan Attari

Maha Basaddiq

Moylin Yuan

Zaynab Kriouech

Digital Programmer

Michal Jurgielewicz

Research Photography

Danko Stjepanovic

Research and Editorial Assistants

Alya Osman

Sundos Alsheebani

Community Outreach

Anam Aziz

Misbah Tanweer

Mohammed Aziz

Nandana Mukundun

Powered by Froala Editor