04/03/2025

Living Continuity: Urban Workshop 2_Immersive Methods: tracing and foregrounding past-present ecologies

The SAT Research Initiative invites you to the second installment of Living Continuity: Urban Workshop Series in Jubail, Sharjah. Building on our exploration of our role as urban actors within the layered histories and evolving ecologies of a neighborhood, this series brings together artists, researchers, and writers whose practices are deeply rooted in lived experiences. Together, we will explore ways to ground research from a place, while remaining sensitive to it.

Applications are now open for "Immersive Methods: tracing and foregrounding past-present ecologies", led by anthropologist Neha Vora and artist Richi Bhatia. Join us on April 19, 2025, as we explore the lifeways of urban transformation—documenting material traces, collecting objects, and uncovering emerging narratives. Through discussions and self-guided observations, this workshop invites you to engage with urban spaces, recognizing them not only as human-centric environments, but as shared spaces shaped by multispecies connections and material memory.

View the full program and schedule here.

Click here to register.

03/06/2025

Living Continuity: Urban Workshop 1_Navigating Neighborhoods Through Emotion

The SAT Research initiative invites you to join us in Al Jubail, Sharjah, for a series of urban workshops this spring, as part of our ongoing project, Living Continuity. This series calls for an examination of our roles as urban actors as we move through the convergence of social, economic and urban layers of a neighborhood. We will explore what it means to situate research from a place — drawing on methodologies developed by artists, researchers, and writers who ground their praxis in lived experiences.

We are now accepting applications for "Navigating Neighborhoods Through Emotion" led by writer and creative instructor Bhoomika Ghaghada on March 22, 2025. Employing tools that interweave fiction writing with embodied experience, the workshop invites participants to reimagine the urban environment and their relationship to it. By shifting the lens to show that cities are more than static landscapes—rather, they are lived, felt, and continuously reshaped by our presence—the workshop also encourages a deeper understanding of the power we exert.

View the full program and schedule here.

Click here to register.

08/29/2024

Collective Practice: Roundtable 1_Community Interdependence and Urban Animal Welfare

The second series of our community building program 'Collective Practice' will explore questions around urban animal welfare in the UAE and the urban liminality and challenges experienced by their caregivers. Through a selection of readings and roundtable discussions with scholars, activists and residents we will gather to discuss potential pathways towards seeding responsibility, cultural shifts and collective action towards urban animal and community welfare giving. Discussions will be facilitated to engage scholars, community volunteers and rescuers, and organizations respectively to share perspectives on the complexities of urban animal welfare in the UAE.

The program has limited seats for participants to facilitate focused discussions over the course of two months and produce a shared and developed outcome. Each session will integrate selected readings to inform its dialogue and discussion. We encourage applications from individuals who are currently engaged in various forms of urban animal care and rescue, community organizing and urban design interventionism.

'Collective practice' is aimed to hold space for exercising alternative actions and approaches to research. By sharing literature, knowledge and experiences we hope to challenge the silos of socio-urban discourse and relate to others through connection and active understanding.

This series is part of a longer term initiative to foster a balanced civic forum to stimulate dialogue and collaboration. It is intended to create a space for exchange across communities with common interests improving towards urban conditions and critically examining urban policies.

View the full program and schedule here.

Click here to register.

05/31/2024

Collective Practice: Reading Circle 1_Palestinian Walks

The SAT Research initiative invites you to our community building program 'Collective Practice', beginning with a series of fortnightly reading circles where we will gather to read, learn and unlearn together. Collective practice is aimed to hold space for exercising alternative actions and approaches to research. By sharing literature, knowledge and experiences we hope to challenge the silos of socio-urban discourse and relate to others through connection, active understanding and solidarity.

Our first reading circle will center the book 'Palestinian Walks' by Raja Shehadeh. Set across six walks taken between 1978 and 2006, the book traverses the expropriation of native lands to illegal settlements.

We will meet on every alternative Monday from June 24 - August 5, 2024.

REGISTRATION DEADLINE: June 13, 2024

Click here to register.

03/28/2024

Resident Focus Group_Summer 2024

The SAT Research initiative, 'Living Continuity: a collective inquiry', invites you to participate in our ongoing activities on place-making and community building. Join us to envision and express our relationship to the city in our resident focus group sessions this summer where we will create new tools and processes to engage in the city. If you are a resident of Sharjah and interested in contributing to collective learning on our relationship to our neighborhoods and communities, we'd love to hear from you. Register your interest to participate in this series of meetings that will be planned from May-July 2024 to receive details and updates .

Click here to register .

02/18/2023

Living Continuity Sessions 5 and 6

Panel 1: The Urgency of People-Centred Planning and Praxis-based Alternatives

For this session, we look critically forward and explore work that challenges the current frontiers of architecture and urbanism. How can praxis enable critical engagement, and what does it reveal around current issues of access, exclusion, precarity and participation in neighbourhood?

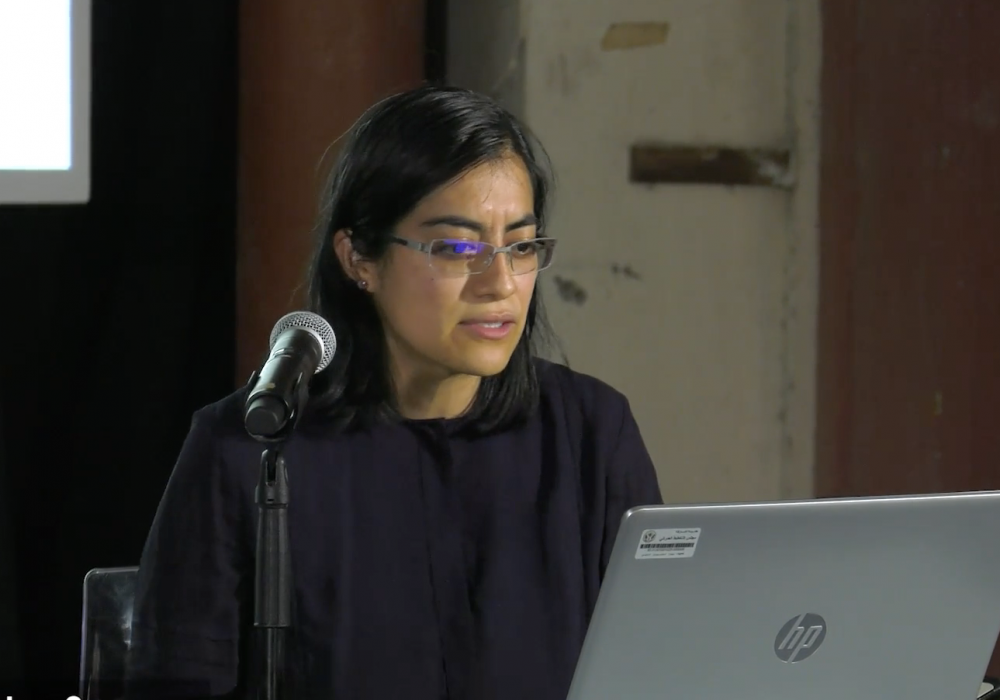

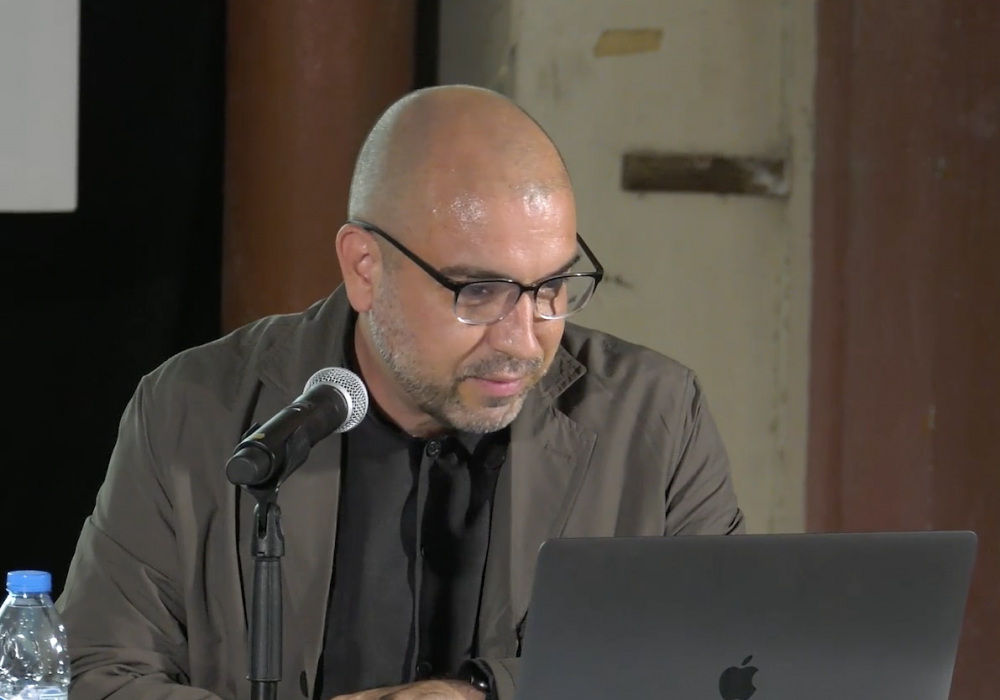

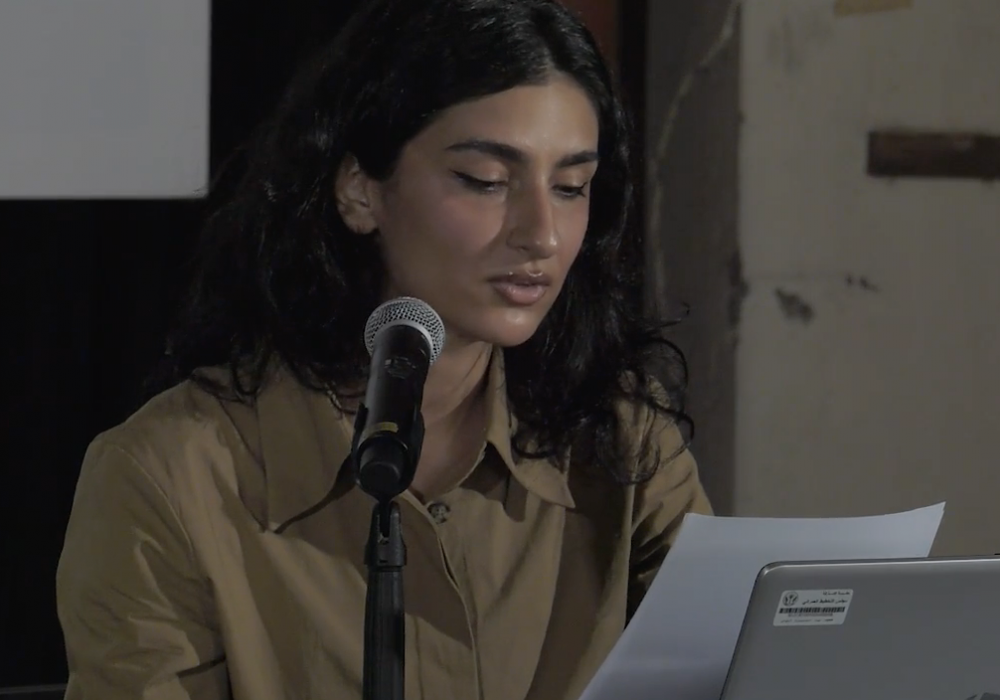

Panelists: Arshiya Syed, Jason Carlow, Najia Fatima, Paulina Yeal Cho

Convener: Sharmeen Inayat

Discussant: Beatriz Itzel Cruz Megchun

Panel 2: Participatory Research and Lessons in Community Interdependence

In this session, we will explore the importance of amplifying and enabling community voices. What are the challenges, incremental and transformative actions necessary to challenge current systems that exclude and marginalize the global majority? How can modes of research support modes of resistance?

Panelists: Maitha Alhammadi, Marcos Parga, Ailo Ribas

Convener: Sharmeen Inayat

Discussant: Beatriz Itzel Cruz Megchun

We are committed to fostering community building through ongoing collaborative engagement and critical discourse. Registration for individuals who are interested to attend and participate is open.

View program details here.

02.02.2023

Spring 2023 Program Announcement

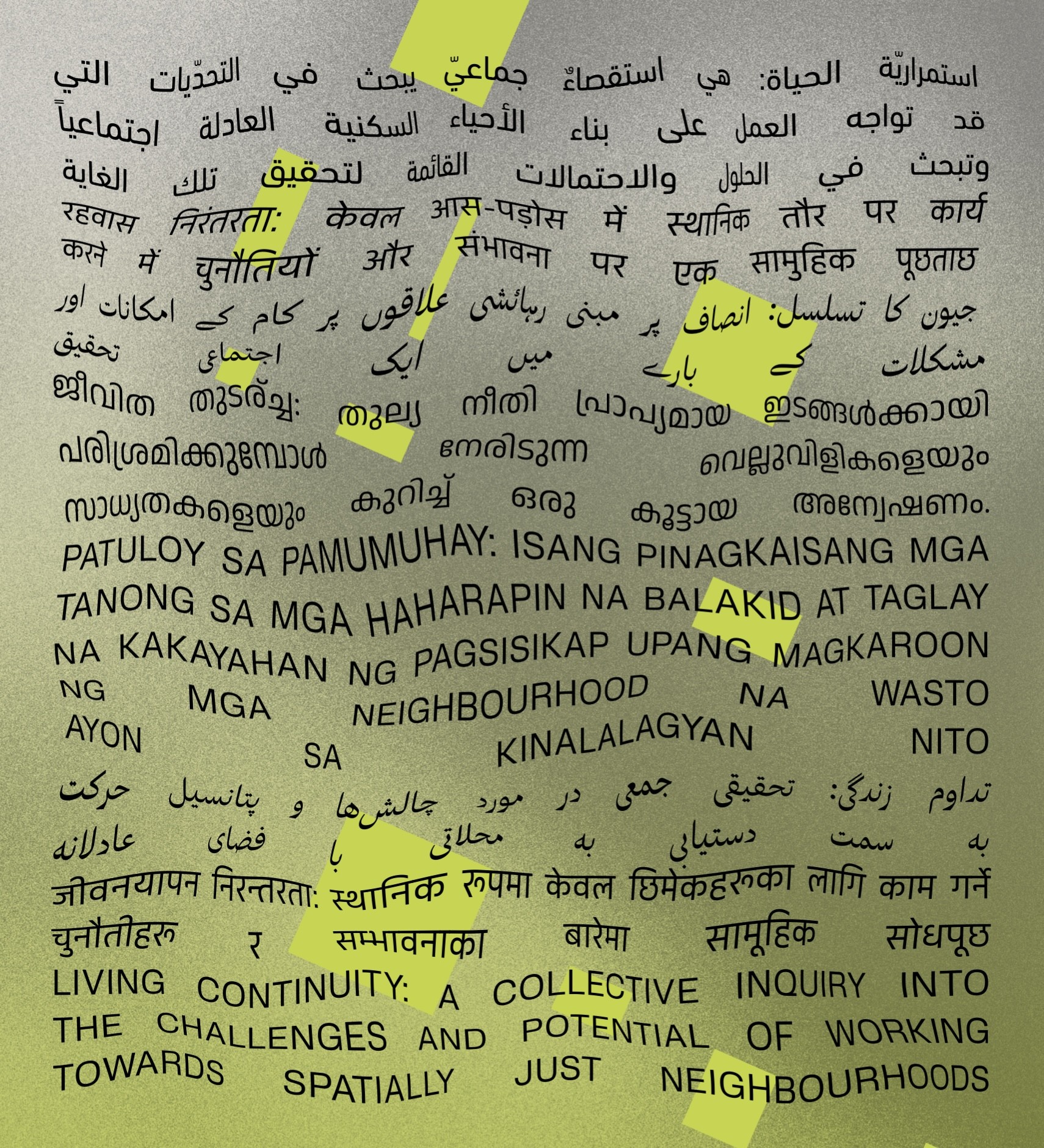

Living Continuity is a collective inquiry into the challenges and potential of working towards spatially just neighbourhoods. In current urban policy debates, the neighborhood has emerged as an important scalar construct to understand the systems and processes that shape communities and ecosystems. This calls for re-examining the denotations and connotative dimensions of the terms 'neighbourhood', and 'community' beyond the romanticised and the normative. In the global context of pervasive neoliberal urbanism, cities that are planned and grow on principles of zoning warrant accelerated segregation, expulsion and homogenization. Urban expansion and renewal thus yields disproportionate access to and distribution of environmental wellness, urban commons, social health and mobility. The tension between renewal vs expansion which occurs at this scalar level also raises questions on how to secure lived continuity, intersectional diversity, and social cohesion. How can interlocutors, respondents and residents facilitate and advocate for inclusive, decolonial and sensitive discourses around urban policy and education given socio-political limitations and challenges?

This line of inquiry will continue to be explored through a research exhibition featuring roundtables, knowledge exchange and supplementary tools from February 18th–April 30th 2023 at the Al Jubail Vegetable Market in Sharjah and online on the SAT Research Initiative webpage. We will reflect on how to broaden our understanding of praxis-based alternatives as well as how to amplify people-centred approaches through insights on interdependence, plurality and spatial practice. Stay posted for announcements and details on how you can participate. Living Continuity is the inaugural discursive series organized by the SAT Research Initiative, one of the core programs of the Sharjah Architecture Triennial. The project is curated by Sharmeen Inayat, Research Curator of SAT Research Initiative and features contributions from Ailo Ribas, Alfonse Chiu, Arshiya Syed, Beatriz Itzel Cruz Megchun, Bhoomika Ghaghada, Haitham Issam, Jason Carlow, Khaled Alawadi, Khaled Galal Ahmed, Maitha Alhammadi , Marcos Parga, Mona El-Mousfy, Najia Fatima, Paulina Yeal Cho, Yasser Elsheshtawy, Tariq Miah, Martin Abbott + Jennifer Minner, Frederik Weissenborn + Aude Azzi, Juan Roldan, Bhakti More, George Katodrytis, Muhammad Aziz, Abu Dhabi Public Spaces Project, Jumanah Abbas, Leon Duval, and Ashraf Salama + Florian Wiedmann.

12.08.2022

Register to attend Living Continuity Seminar Session 4 (Online) to be held on August 24th, 2022

SAT Research seminars resume with Session IV which will convene online on August 24th, 2022. Living Continuity is a collective inquiry on the challenges and opportunities of working towards spatially just neighbourhoods. Session IV aims to explore the temporal dimension of housing through indicators of social cohesion and socio-spatial attributes that resist transit. Dr Yasser Elsheshtawy expands on a case study analysis of folk houses in the UAE, how they became a testament of inhabitants asserting their presence and rootedness in the midst of a constantly changing cityscape and the lessons they provide. Dr Bhakti More shares her study comparing four residential neighborhoods in Dubai to understand the concept of residential stability, social cohesiveness and the influence of shared spaces among expatriate residents in neighborhoods in Dubai.

Committed to fostering community building through ongoing collaborative engagement and critical discourse, registration for individuals who are interested in attending and participating in the discussion with the invited speakers is open. To RSVP, please send expressions of interest to info@sharjaharchitecture.org. The session will be held online on August 24 at 6:00 PM GST. Confirmations of your registration along with the webinar link will be sent by email on August 21.

View full programme.

02.06.2022

Call for Proposals (Essay Abstracts)

This call for proposals invites contributions to the first installation of SAT Research. Authors of accepted essays will be commissioned to develop their work for publication. The publication will feature the work of invited contributors as well as authors selected through this open call process. Select commissions may be invited to present their work at a symposium to take place in December 2022 in Sharjah.

While the emergence of local and regional urban centers evolved from an economy of constraints and subsistence, the pervasiveness of contemporary practices that have largely evolved in the Global North has gradually resulted in the rupture of the socio-urban fabric and an excess disconnect with local conditions . There is an urgent need for a radical shift toward urbanism that is responsive to social needs and ecological limits as a matter of survival.

Living Continuity is an invitation to begin a collective inquiry on the challenges and potentialities of working towards a socially and ecologically just urban future beginning at the scale of the neighbourhood. Subject matter that will be explored includes but is not limited to:

1. Social and ecological issues as a result of the development of homogenised neighborhoods and accelerated land use.

2. Proximity and access to neighborhood amenities and green spaces.

3. Spatial practices that shape traditional neighbourhoods. In port cities such as Sharjah, this included responsive and adaptive typologies, urban diversity and compactness.

4. The impact of neoliberal and colonial forces on local conditions through shifting value systems and expeditious expansion.

5. Social rituals reimagined as alternatives to current dominant models.

6. Readings across time, sectors and communities to better understand the issues around and solutions to spatial distribution and access.

7. Social conduits and urban voids as tools of collective efficacy and interdependency.

Format and Focus

Proposals must include a 250-300 words abstract and author biography.

Proposals for the following essay formats are invited to submit:

1. Expository Essay of 2500 to 5000 words. Expository essays are reserved for research-based work focused on Sharjah and the United Arab Emirates or work that draws strong comparisons and parallels to local conditions. 2. Argumentative or Position Essay of 1500 to 3000 words. Position essays are not limited to geographic scope and are open to writing across research, practice and education that provokes new perspectives and offer a critical lens for the subject matter. 3. Visual Essay or Data Story of 5 to 20 visuals: Visual essays are not limited to geographic scope and are welcome to illuminate knowledge and findings that support key ideas in an artistic capacity or through data journalism.

Key Dates [UPDATED]

July 15, 2022: Deadline to submit abstracts and proposals

August 09, 2022: Notifications sent to authors of selected proposals

November 05, 2022: Deadline to submit the full-length drafts

November 30, 2022: Editorial review sent to authors

December 21, 2022: Deadline to submit final essays

Submission

Authors will be asked to grant copyright for publication, symposium proceedings, exhibition purposes, and online and print dissemination. The Sharjah Architectural Triennial is a not-for-profit organisation.

Authors must be able to furnish requested permissions for any third-party materials included in their paper.

This is a multi-disciplinary initiative that strives to be inclusive. Contributions from fields beyond the realm of architecture and urbanism including the social sciences and the arts are strongly encouraged. New perspectives on methodologies, marginalised voices outside the realm of academic research and local knowledges from the Global South are also strongly encouraged.

All submission documents must be sent as a Microsoft Word file via email to the editor at sharmeen@sharjaharchitecture.org.

12.03.2022

Register to attend SAT Research Launch – Living Continuity, Seminar Sessions 1, 2 and 3

SAT Research's first seminar will be held on March 19th, 2022. Titled, Living Continuity: A Collective Inquiry, This installation focuses on local challenges to preserving robust, sustainable and inclusive neighbourhoods. Questions we will be asking include: How can we reimagine rapidly eroding regional sensitivities and knowledge systems? How can architecture and urbanism practitioners, educators and stakeholders begin to tackle precipitous global urbanization while operating in a vast field of economic, political and social demands? Committed to growing a repository of local knowledge production and fostering community-building through ongoing collaborative engagement, we invite individuals who are interested in participating to join our invited speakers and discussants for the full-day event. Please send expressions of interest by March 15. Seats are limited and confirmations of your registration will be sent by email on March 17.

Session I, alternatives to urban expansion, will open the discussion with Mona El-Mousfy's insights stemming from her research-based practice and the application of adaptive reuse methods in Sharjah City, and Khaled Galal Ahmed, who offers alternative solutions to social housing in the UAE to challenge the prevalence of Western housing models. Session II, urban networks as critical space, features Khaled Alawadi's morphological mappings of alleyways in Abu Dhabi and Dubai revealing the potential impact of these micro-networks and Beatriz Itzel Cruz Megchun's framework for design for social interdependence. Session III, forms of community expulsion and exclusion, will conclude the day's sessions with Bhoomika Ghaghada's analysis of the cultural expulsion in the Karama neighborhood of Dubai that questions what is lost when something is redeveloped and Juan-Roldan Martin's observations of urban appropriation and rituals established by inhabitants that defy constructs of imported Western park models in the UAE.

The event will take place at the disused Al Jubail Vegetable Market in Sharjah in a segment of the semi-open, naturally ventilated building. The site, previously slated for demolition after the market was relocated, is currently being programmed by the Sharjah Architecture Triennial and the Sharjah Art Foundation for temporary events and exhibitions. It is planned to be the future home of SAT Research among other institutional activities and public programmes.

View full programme.

Powered by Froala Editor